Wednesday, July 4, 2012

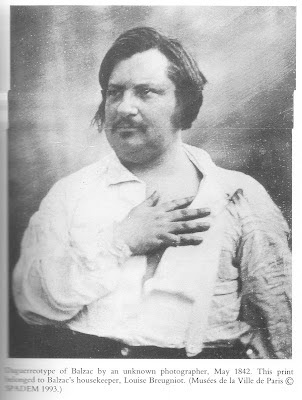

Balzac's Omelette by Anka Muhlstein

One constant in Parisian society during Balzac’s time ( 1799-1850) was the presence of servants: however few or many of them there were and however well trained they may have been, they were always there. Even the modest shopkeeper’s household depended if not on a cook, at least on a housemaid. The only exceptions are the moneylender Gobseck, a pathologically secretive character who cannot abide any curiosity about his life, and Silvia Rogron, who dismisses her cook in a frantic bid to save money, claiming that “she herself cooked ‘to amuse herself.’” As a general rule, in Balzac’s world the quality and appeal of a meal are as much the product of a servant’s talent as her honesty and the relationship she has with her employers. These servants are inevitably women, because, as mentioned above, there are not active chef’s in Balzac’s work. . . .

There was inevitably a significant amount of theft among suppliers and staff, and this issue seemed to have obsessed Balzac, unlike Zola, who put his emphasis on how cruelly servants were treated. The conservative Balzac felt that “in every household the plague of servants is nowadays the worst of financial afflictions,” and he showed little indulgence for the servant who was effectively a “domestic robber, a thief taking wages, and perfectly barefaced.” According to him theft was so widespread in Paris that it required round-the-clock surveillance. Only the greatest misers and women who were very careful with their housekeeping money avoided this bloodletting.

The fact that Madame Marneffe’s household recovers is due to Lisbeth, also known as Betty, her lover’s cousin, who takes things in hand. The first task Betty assigns herself is to dismiss the disgraceful maid, because she knows that the servants have set up a secret toll system between the market and their master’s table, even going so far as to persuade shopkeepers to increase their written receipts by 50 percent. The only way to run a household economically is to watch over the cook and teach her to do her buying in the market instead of going to suppliers who have no qualms about pumping up the bill.

That is what the formidable Betty does when she reorganizes her friend Valerie’s house. A relation of hers once worked for the bishop of Nancy, a telling detail because, according to Balzac, doctors and men of the cloth were great specialists in gastronomy. “So she had brought from the depths of the Vosges a humble relation on her mother’s side, this very pious and honest soul. . .Fearing, however, her inexperience of Paris ways, and yet more the evil counsel which wrecks such fragile virtue, at first Lisbeth always went to market with Mathurine, and tried to teacher her what to buy. To know the real prices of things and and command the salesman’s respect; to purchase delicacies [unaffected by the seasons], such as fish, only when they were cheap; to be well informed as to the price current of groceries and provisions, so as to buy when prices are low in anticipation of a rise, - all this housekeeping skill is in Paris essential to domestic economy. As Mathurine got good wages and many presents, she liked the house well enough to be glad to drive good bargains.”

Going to market guaranteed the best price but also the best quality, and this was true right up until the twentieth century. Proust’s narrator (probably persuaded by his mother) sends the family cook there to buy the necessary ingredients to make her beef en gelee a masterpiece.

But going to the central market was no mean feat. When Balzac was planning to hire a cook who his sister had to let go for financial reasons, he made it a condition that she agreed to buy from Les Halles as restaurateurs and fruit sellers did. She refused, because it took exceptional energy to get up at dawn and barter with the vendors. When money was very tight, he was therefore reduced to hiring a woman who came in on Mondays to prepare meals for the entire week – despite his horror of cold meat. When he reached the end of his beef or mutton dish, he had to make do with bread, cheese, and potatoes like the Irish.

The marketplace of Les Halles was in fact a building site at the time. In 1811 Napoleon had started a project to replace the old wooden hangers and their stalls, open to the four winds, with a modern construction, but the work was not finished before the Second Empire. The regulars at Les Halles treated themselves to eau-de-vie spiked with pepper, and the overall noise and commotion was hardly designed to attract the fainthearted.

Even an old Parisian like the perfumer Birotteau, when looking for the hazelnuts he needs for his hair oil, has trouble making his way through the labyrinth “of slums which are, as it were, the entrails of Paris. Here countless numbers of heterogeneous and nondescript industries are carried on; evil smelling trades, and the manufacture of the daintiest finery, herrings and lawn, silk and honey, butter and tulle, jostle each other in its squalid precincts. Here are the headquarters of those multitudinous small trades which Paris no more suspects in its midst than a man surmises the functions performed by the pancreas in the human economy.” Cousin Betty, who is afraid of nothing, is commendably successful: to Madame Marneffe’s tremendous credit, her dinners bring together artists, politicians, and her lover’s friends.

Sadly, Cousin Pons and his friend Schmuckle lack this attention to detail and knowledge of current prices when they try to keep an eye on their concierge, Madame Cibot, who cooks their meals and, in doing sop, leads them to ruin. She boasts to her husband that she has amassed two thousand francs in eight years thanks to her cunning and talent. In fact, rather than going to the butcher, she rummages through the stalls at a regrattier, who buys leftovers from nearby restaurants. With a fiercely discerning eye, she chooses the best-looking debris of chicken or game, fish fillets, or eve boiled beef, which she dresses up with finely sliced onion. Using this technique, she cooks such strong-smelling sauces that her lodgers never complain, and she makes them pay three francs “without wine” for these dinners, a sizable sum if w consider that, in a modest but acceptable restaurant, a meal with a small carafe of wine cost a maximum of two francs.

This sort of misadventure was not likely to happen to Madame Guillaume, the draper’s wife in At the Sign of the Cat and Racket. She is so horrified at the thought of potential waste that not only does she trust no one else to pour oil over the salad, but she herself does it with such a sparing hand that she barely moistens the leaves. By way of desert, she serves Gruyere – which was a poor man’s cheese at the time – and Guyere so old that her staff as fun carving the date on it.

Less meticulous women were either ignorant of the full extent of the damage or resigned to be robbed by their cooks, and, in Paris, the cooks were cheekily aware of the fact. It is hardly surprising that it was essential for well-brought-up young ladies to learn – from watching their mothers – to scold the cook. Otherwise, they would soon find that a serving girl who “entered their service without effects, without cloths, and without talent, has come to get her wages in a blue merino gown, set off by an embroidered neckerchief, her ears embellished with a pair of ear-rings enriched with small pearls. Her feet clothed in comfortable leather shoes which give you a glimpse of neat cotton stockings. She has two trunks full of property, and keeps an account at the savings bank.”

Balzac’s Omelette; A Delicious Tour of French Food and Culture with Honore de Balzac by Anka Muhlastein; Other Press, N.Y. 2011

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment